Israel's Delta Wave: How a highly-vaxxed country rode out Delta

Waning immunity, booster shots, and maybe a restored herd immunity: What happens when a highly-vaccinated country had a big Covid wave?

In my last article, I wrote:

In Part II in the next couple of days, I’ll start to think about what it all means.

Well, it’s been a little longer than a couple of days. More than two months, actually. I’d like to apologise but I have a good excuse.

His name is Maor and he was born nearly 12 weeks ago. The journey to his birth is a long and dramatic story that maybe I’ll tell one day. For now we’re happy to have him.

But I’m back now, or as back as anyone ever is after they become a parent. Thanks for your patience.

Israel’s Delta Wave: How it all played out

In the last few weeks, the Covid picture has completely changed in Israel. Israel suffered from a Delta wave that had the highest new daily coronavirus cases per capita of any country in the world in September.

What about Israel’s high vaccination level?

Despite what you might think, Israel no longer has a high percentage of vaccinated people compared to other industrialised countries. It was still just about true in July, but in October it just isn’t true anymore.

So why might you think it does? Well, Israel vaccinated its population early, so a lot of grounding bias comes into play; people heard Israel was the most vaccinated country back in March, but now in October a lot of industrialised countries have caught up. Equally, the perception that Canada and France have poor vaccination rates, which was true in the spring, is now also outdated

The other factor is that Israel has a very young population. More than 20% of Israelis are aged 11 or younger, and are currently ineligible to be vaccinated. In the USA and the UK, for example, under-11s are just 13% of the population. That means that the absolute maximum that Israel could have reached in vaccination terms was like 78%, compared to 87% in the United States.

But it’s not just a question of how many people were vaccinated. It’s also relevant when they were vaccinated.

Waning protection from vaccines

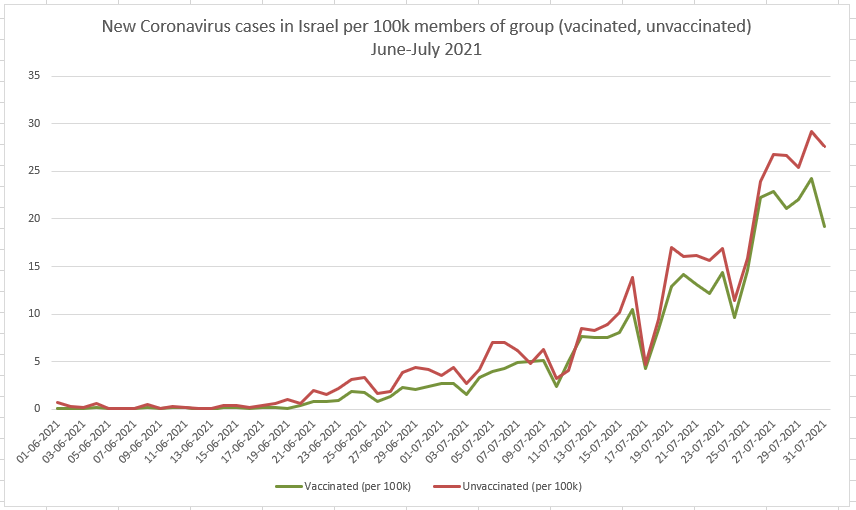

When Delta began spreading in Israel among highly-vaccinated populations, it looked a lot like it might have evolved to escape the immunity that the vaccines induced. Sure, Delta was a lot more infectious, but that didn’t seem enough to account for the sharp rise in infections among the vaccinated even when compared to the unvaccinated.

In fact, the vaccinated population was testing positive for the coronavirus at only slightly a lower rate than the unvaccinated. Of course, testing positive doesn’t mean you have symptoms or even that you’re very infectious to others. But it was still a worrying change.

There were lots of confounders in this data. For one, the unvaccinated population in Israel is mostly children, and children catch and transmit the virus less easily than adults do. Still, even controlling for age, it seemed that the vaccines were providing only limited protection against catching the virus.

But it turned out that Delta wasn’t “evading the vaccines” at all. People who’d been recently vaccinated were still well protected against the variant, but vaccine effectiveness waned over time against any variant of the coronavirus.

Israel had vaccinated most of its adult population much by March, and most of its vulnerable people by late January, making it one of the first countries to test the effectiveness of vaccine immunity over time.

Some context here is important. The coronavirus vaccines, all of those used in the West at least, were extraordinarily effective at preventing infection. What I mean by that is that they supposed all expectations, preventing infection with an effectiveness of 90-97%. That’s wild, and pushed Israel past the population immunity threshold for the virus in the spring. Vaccines, for a brief moment, seemed like they’d end the pandemic completely with no more need for mitigations.

But the combination of the more infectious Delta variant and the reduced protectiveness of the vaccine led to a situation where more vaccinated people than expected were catching Covid and getting seriously sick too.

Another contributory factor was the protocol. Israel followed the manufacturer’s instructions, giving its two Pfizer doses 3 weeks apart. Some countries, like the UK, chose to delay the second dose, giving it 8-12 weeks after the first. They did this mostly to give as many people as possible a first dose quickly, but scientists speculated that the longer interval might give longer-lasting protection.

Evidence from the UK shows that this theory is true. In reality, 8 weeks is the sweet spot interval between Pfizer doses that gives the most sustained protection against the coronavirus. Israel hasn’t changed its protocol and is sticking to 3 weeks, but the UK’s decision to opt for 8 weeks initially is probably helping them keep the vaccines effective for longer.

Boosters for Everyone!

By the beginning of August, it was clear that there were both too many infections among the vaccinated, and too many unvaccinated adults (6-7% of over 60s are still unvaccinated) for Israel to just ignore Delta. Serious cases were rising too fast again and the hospitals were feeling the strain.

The country did reintroduce some mitigations, like public masking, the Green Pass and modest limits on events. But mostly it pinned its hope on booster doses of the Pfizer vaccine.

Israel initially offered boosters only to the over-60s, but within a few weeks they were open to anyone who’d been vaccinated at least five months previously. Take-up among older age groups was high, though not universal.

The results were dramatic. The booster dose seemed to produce ten times the antibodies of the second dose.

This also translated into a dramatic drop in infection among boosted people. An analysis by Israel’s Health Department, published a few days ago in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that over-60s who’d been boosted were nearly 20 times more protected against serious Covid-19 than those who had been vaccinated but not boosted. The same study found that the booster also increased protection against coronavirus infection too, with boosted people being 5-11 times less likely to catch the virus than people who were vaccinated six or more months ago.

It’s pretty clear from the numbers, too.

Compare this graph from July, where most of the daily cases were among the vaccinated people….

…with this one, from now (yeah, they redesigned the graphs too). More than two thirds of daily cases are among the unvaccinated now. A quarter or so are among people vaccinated more than six months ago. And only 4% of new cases are in the 40% of people who’ve had a booster dose.

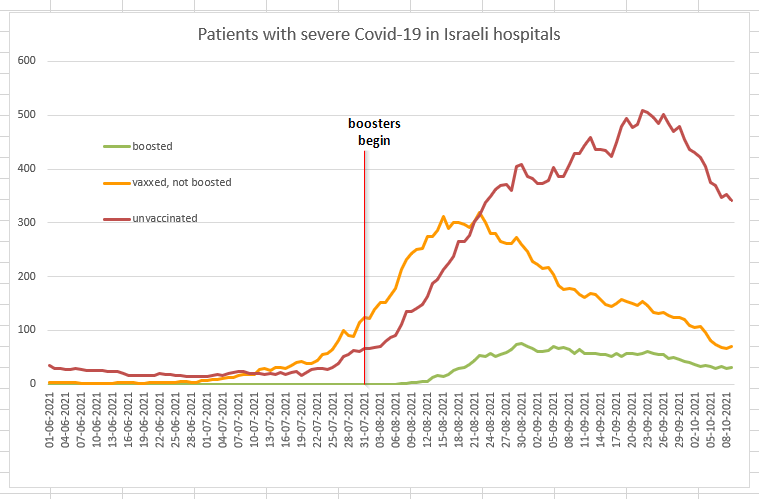

The picture is mirrored in hospitals. Throughout July and early August, there were more vaccinated people in hospital with severe Covid-19 than unvaccinated people. That’s not, in itself, a surprise when 93% of over-60s are vaccinated.

But within a month of the booster programme beginning, the number of vaccinated people in the hospital dropped sharply. The number of unvaccinated people in hospital, though, kept shooting upwards until October.

Why did the yellow line, the vaccinated but unboosted group, drop so early? For the simple reason that millions of Israelis got their boosters and left the group. In mid-August, there were 4.9 million Israelis in the ‘yellow' group. Today, there are just 2.1 million, with the rest joining the boosted greens. But note that the green line barely moves despite the group itself swelling in size. Because the boosted people aren’t getting seriously sick.

And now it looks like the wave has broken. With boosters cutting infection chains by making so many more people immune from catching the virus, case numbers are collapsing and Israel feels like it might be back to a form of population immunity.

Of course, the NPIs (non-pharmaceutical interventions, like indoor masking and vaccine certificates) are still in effect. The next challenge will be when these measures are lifted.

What about ‘natural immunity’

Back in July, I pointed out from Israel’s numbers that it looked like past infection was more protective against Delta than vaccination:

Well, it’s hard to say for sure because of confounders in the data, but it looks like recovered people — people who had tested positive for the coronavirus in a past PCR test — are massively under-represented. Recovered people are around 9% of Israel’s population, but they’re less than 1% of current cases….

I wouldn’t be surprised if natural infection turned out to be more protective against variants than spike protein vaccination. It makes sense that the body’s immune system would find more ways to attack the whole pathogen and would recognise different parts of it compared to the changing spike in variants.

Of course, the whole point of vaccination is to be better than catching the disease. Catching Covid is a bad way to stop yourself from catching Covid.

This remains the case in the data, with recovered people seeming to be well protected. They’re like 14% of the population and only about 1% of cases. Now, though, we know why: it wasn’t necessarily a feature of Delta, but it was that vaccine-induced immunity was waning.

The only thing, though, is it looks like infection-induced immunity also wanes over time, with people who got Covid a year ago more likely to catch the virus than those who caught it this year. Dvir Aran PhD crunches the numbers in this Twitter thread:

Israel now no longer considers recovered people to be immune for life; they’re expected to get a single vaccine dose as a booster six months after their recovery. Infection-induced immunity is good, but adding a vaccine dose is the best of both worlds

Not just waning immunity

It wasn’t just waning immunity. Israel’s data in June and July was artificially pessimistic, because in those months the virus was spreading mostly in cities with very high vaccination rates compared to the national average. Proportionally more vaccinated people were getting sick because that’s where the outbreak was.

Conversely, the virus spread to less-vaccinated towns in September and that made the the booster programme seem even more effective as unvaccinated communities fell sick.

Boosters forever?

We don’t know now how long the protection from the booster will last. It might be a long time; many vaccines have a three-dose protocol. Maybe this booster will see us through for a couple of years, or even longer.

But if not, I don’t think we can keep inducing massive antibody levels by vaccination every six months in order to keep community transmission low. Variant-specific boosters annually, like the flu jab, sure. Or perhaps we need some NPIs like occasional indoor masking and better indoor ventilation for the long term. And we certainly need more therapeutics like Merck’s molnupiravir, better and cheaper access to home testing and all the other tools too.

Boosters are good; vaccines are great

Just to finish on an important point here: even without a booster, vaccines are still saving masses of lives and keeping people out of the hospitals. The graph below shows severe hospitalised Covid-19 cases in Israel among the over-60s, but normalised to the size of each group.

Unvaccinated people are hospitalised at a higher rate. Once in hospital they deteriorate faster and are more likely to end up on ventilators and, often, die. A booster significantly improves the effect of the vaccine on people who were vaccinated more than 6 months ago, but even without the booster, the difference between vaccinated and unvaccinated outcomes is very clear. So get vaccinated. It’s worth it.

Thanks for reading and thanks again for your patience while I was away. Normal service will hopefully be resumed from now on.

Any thoughts, comments or criticism welcome in the comments section, which is open to non-subscribers too this time.

If you’ve found this article interesting, please consider signing up or even becoming a full subscriber.

Still, it appears that infection induced immunity wanes far more slowly than does vaccine immunity. But the more important questions are, how often do reinfections among those with infection induced immunity progress to hospitalization or death? Are serious reactions to the vaccines more common among those with infection induced immunity than those who are virus naive?